A gradual but inevitable descent into cricket-based loathing and bile.

Darren Lehmann And The Curious Case Of Too Many Mitchells

Imagine a football team lining up with two Peter Crouchs up front. Or perhaps one Peter Crouch and one Andy Carroll. Or Carroll alongside that really tall guy who plays cricket for Pakistan but whose name we can never seem to remember [Mohammad Irfan – Ed]. Regardless of the combination of freakish monsters that you finally settle on, your strike force would still be an affront to nature itself. It just doesn’t make sense to have two players filling the exact same role, particularly when that role is basically ‘enormous lump to hoof the ball at’. And yet this is almost exactly what Australia have just spent four Ashes Test matches doing.

The question of balance in a bowling attack is something that is often taken for granted. While a batting order will be carefully planned, with an appropriate mix of blockers, dashers and gingers, picking the bowling attack usually consists of working out how many spinners you need and then selecting fast bowlers from best to worst until there’s no more spaces left in the team.

Having Mitchells Starc and Johnson in the same side sounds undeniably appealing on paper. After all, if one left arm fast bowler caused England so many problems in 2013/14, surely two would do twice as well? This theory ties in with the ‘attack at all times’ approach of Darren Lehmann, the one that has so spectacularly failed this summer, and largely overlooks the fact that if one left arm quick isn’t making an impact then the other probably won’t either, placing an enormous strain on the rest of the bowling attack.

Without Ryan Harris, that bowling attack simply couldn’t cope. Josh Hazelwood was bigged up before the series started in poorly thought out prediction pieces but looked exactly like what he is: a young bowler still learning his trade, particularly outside of Australian conditions. Asking him to do that while also covering for the various sins of the Mitchells was clearly too much. Add in a fourth seamer who either couldn’t be bothered (Watto) or was also very much learning on the job (Mitchell Marsh) and it’s no surprise that things fell apart.

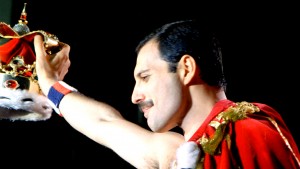

With Josh Hazelwood nipping to the toilet, the rest of Australia’s seam attack took the opportunity to pose for photos prior to the first Test.

The issue of ‘roles’ and ‘bowling units’ is a complicated one, a messy melting pot of individual and collective performance. Somewhere in the 51allout vaults is a never-released article examining whether there is such a thing as a ‘halo effect’ in cricket. While we don’t want to regurgitate it all here – there is a reason it remains unreleased, and it’s not because we’re saving it for the 20th anniversary re-release of the site – it did show that Mitchell Johnson has noticeably worse numbers in matches without Ryan Harris: 96 wickets at 20.71 and a strike rate of 39 alongside Harris, 206 wickets at 31.43 and a strike rate of 57 without him.

This does lead into an argument around cause and effect: did Johnson bowl better because Harris was there? Or was Harris just fit at the times that Johnson was actually bowling well? Like Peter Nevill, we’ll leave that straight one well alone and carry on with our point: there just isn’t space in the Australian bowling attack for two streaky left arm quicks to bowl short aggressive spells. If the third quick was of the quality of Ryan Harris it might have worked, but he wasn’t and it didn’t. The selectors failed in their duties by either not noticing or just plain ignoring this crucial fact.

Quite what Peter Siddle has done to piss off Darren Lehmann and chums isn’t all that clear. Maybe they just really hate bananas. Or perhaps Siddle’s control of line and length – he’s the very definition of a workhorse bowler – doesn’t fit in with the team’s strategy, in which case the strategy is to blame. Either way, Siddle and his vast experience of English conditions would have brought the control that the rest of the seamers found almost impossible to achieve. Not selecting him was a clear and obvious mistake, despite the obvious allure of having the two Mitchells in tandem. Of course, choosing which one of them to exclude is exactly the sort of dilemma that top international selectors get paid vast fortunes to solve.

After the Ashes, the Australian rebuilding process starts in Bangladesh, exactly the sort of place that needs hard working seamers capable of bowling long spells. Last time England were there they used two spinners and made Tim Bresnan do most of the heavy lifting, a role that his previous work in B&Q left him perfectly equipped for. Realistically, a second spinner will come in alongside Nathan Lyon, leaving Mitchell Marsh plus two quicks. And if they’re also Mitchells we might have to bet our meagre gin allowance on a Bangladesh win.

No Comments

Post a Comment