A gradual but inevitable descent into cricket-based loathing and bile.

England’s Number One Number Three

As with all statistics, analysis of cricket trends and performances often needs to be taken with a large pinch of salt. Beyond the results, do the numbers really matter? Once the margin of victory has been printed in the record books and the trophies engraved with the special little tool by the man in the darkened room (are there female engravers? If so, please do get in touch), do the little numbers that contribute to the outcome actually mean anything?

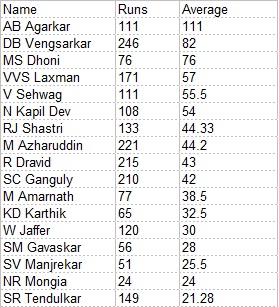

Sport at its best is a thing of beauty and passion; body and mind in perfect harmony. Won’t calculating Michael Vaughan’s average in overseas matches when batting in the middle order (1132 runs at 34.30, an average of six runs per innings fewer than John Crawley and only three more than Tim Ambrose) diminish the memory of his cover drive? With enough data, can’t any argument be formed, if you manipulate the factors sufficiently? As Table 1 shows, Agit Agarkar is unequivocally a better batsman than Sachin Tendulkar.

Well, cricket has always been about the numbers, probably even when matches were organised in London parks and on Sussex downs solely for the purpose of wagering between aristocrats. People don’t buy Wisden for photos of elegant attacking shots. Certain numbers are ingrained in the brains of cricket fans from Auckland to Antigua to Ahmedabad: 99.94, 501*, 19-90. Hell, even 51, although this generates worse memories for Englishmen than those sixteen weeks of summer 1991 when Bryan Adams was at number one in the charts.

Looking at the statistics that lie beneath the stories helps to provide the objectivity to the arguments that form any cricketing discussion. However they rarely conclude anything: they don’t show that black is not white and they can’t predict that England will be bowled out by Jerome Taylor.

Furthermore, statistical analysis certainly won’t prove that Bradman was better than Tendulkar (or vice-versa, if there are any Indians reading) or McGrath better than Holding. And nor should we want them to. The subjectivity of these issues relies on such qualitative matters as memory and the belief in what we see with our own eyes. A 70-year old straw hat-wearing Yorkshireman will always advocate Trueman in the same way that those who only know of Wasim and Waqar will state that they were the greatest.

But we here at 51allout enjoy our statistics. They can generate debate and highlight interesting aspects of the sport. We will leave Kevin Pietersen’s performance against left-arm spinners for another day (warning: this will contain references to Ryan Hinds), but in tribute to Ian Jonathan Leonard Trott, herewith a quick look at England’s problem position No.3 over the last twenty years.

That’s position No. 3 in the batting order, not problem No. 3, which is probably the back-up spinner, or if the ECB are concerned, the level of natural light before the umpires can consider discussing the possibility of having a debate about when to turn the floodlights on.

The most successful in this position, globally, have had various characteristics, whether obdurate (Dravid), fluid (Sangakarra) or just damn, frustratingly, great (Ponting). In the 1980s, Gower and Richards both batted at No. 3 regularly, but so did Boon and Gatting. Apart from scoring runs by the bucketload, the only common trait is the need to be flexible and ready.

Over the last twenty years 13 different players have batted at least 10 times at No. 3 forEngland. So we’re discounting nightwatchmen (Fraser, Hoggard), temporary changes to the order (Gooch, Pietersen) and Jason Gallian.

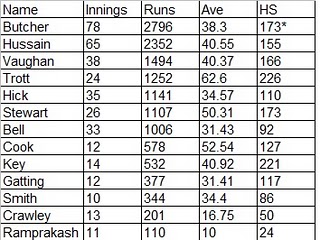

The simple stats are shown in Table 2. Here it is clear that the position has been mostly held by seven different batsmen, including Trott.

Only Butcher, Vaughan and Hussain, with six apiece, have scored more 100s than Trott in this position, all of whom have played significantly more innings. The basic stats in Table 2 demonstrate Trott’s success in the role. Unfortunately, this does take into account Trott’s innings at Cardiff for example, which was actually scored from No.4 in the order. He also scored 69 at Centurion batting behind Anderson, with the score on 16-2 when he came to the wicket.

If the key to a good No. 3 is flexibility and adaptability, then this is evidenced by the situation in which he has scored his centuries:-

-

Lord’s v Bangladesh, 7-1 (followed by a partnership of 181 with Strauss);

- Lord’s v Pakistan, 31-1 (soon England were 47-5, but a record-breaking partnership of 332 with Broad changed the match);

- Brisbane v Australia, 188-1 (unbeaten partnership of 329 with Cook);

- Melbourne v Australia, 159-1;

- Cardiff v Sri Lanka, 47-2 (partnership of 251 with Cook).

These would suggest that the success of the opening partnership- and indeed the batsmen following him down the order- have little bearing on his scores.

Critics could point to the series in South Africa, where he faced arguably the best pair of strike bowlers in the world in Steyn and Morkel, where his record was 190 runs at 27.14. However he did manage to score 404 runs at 67.33 against Amir and Asif, albeit at home. Perhaps he has not yet had to bat against a world-class spinner, so it will be interesting to watch him play Harbhajan later this summer.

He has been involved in all three of England’s 250+ partnerships in the last two years, in addition to a further 10 100-run stands. Only Hutton, Gower and Gooch have also featured in two 300+ partnerships for England. Oh, and just for the record, he averages 55.65 in ODIs, behind only ten Doeschate and Amla.

Simply put, he’s a run machine and anyone criticising the rate at which he accumulates them is welcome to have the lovely Ramprakash back in the side.

No Comments

Post a Comment