A gradual but inevitable descent into cricket-based loathing and bile.

The 51allout Bargain Basement Book Bonanza: ‘Sundial in the Shade: the Story of Barry Richards’

May we present an award for the most subtitles to a book ever? The winner is this effort by Andrew Murtagh, which according to the Kindle version is called:-

Sundial in the Shade: The Story of Barry Richards: the Genius Lost to Test Cricket

Despite the liberal use of the colon in the title, this is a book that deserves a positive review. Before turning the first page, we should explain about the author. Andrew ‘First Degree’ Murtagh: a bit-part player for Hampshire in the 1970s: the biographer of John Holder and Tom Graveney: the uncle of Middlesex’s very own Tim ‘Meat Is’ Murtagh.

It’s Murtagh on the dancefloor.

The book starts terribly though. Like utterly awfully. We quote:-

“On 21 July 1945, bowlers around the world gave an involuntary shiver. It was not the dawn of the atomic age – the bombing of Hiroshima took place a fortnight later – but the birth of Barry Richards that had given rise to their sense of foreboding.”

It’s like something Alan Partridge would have written. But don’t let this lovely stuff put you off. It’s actually a very good book.

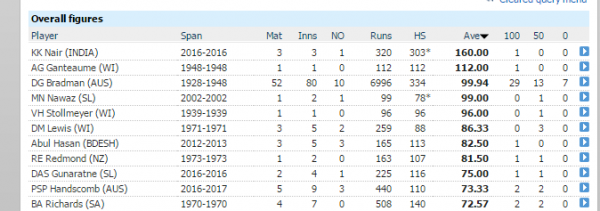

Murtagh makes a compelling case for Richards to be in the uppermost tier of batsmen in the history of the game, possibly second only to Don Bradman. Late in the book Murtagh also acknowledges that Richards’s countryman Graeme Pollock is also more-or-less equal to Richards; the statistics provided certainly back this argument up. The question of how good South Africa would have been in the 1970s, and Richards in Tests, is unanswerable, but the feeling is that they would have been damn good.

But not as good as Peter Handscomb.

Some examples of his excellence? In a Sunday League match at Hull (Hull!) he scored 155* out of 215/2, with no other batsman in the match passing 18. In the 1970/71 Sheffield Shield, he scored 1,538 runs from 16 innings for South Australia, at an average of 109.86. That season, at Perth, he scored 325* in one (five and a half-hour) day, with South Australia 513/3 at close of play. Until Brian Lara scored 390 in a day in a dead match against Durham, no-one had scored so many runs in one day, let alone on day one against Dennis Lillee and Graham McKenzie. In that knock, Richards didn’t even have the benefit of a working slushy machine to cool himself down.

In World Series Cricket, Richards was one of the stars; at last, he could demonstrate his talent and ability against the world’s best in a visible arena, South Africa having been banned from international cricket since his four Tests in 1970. He fared alright. From the ‘Supertests’ against Australia and the West Indies, he averaged 79.14. Contemporaries Viv Richards and Greg Chappell had the next highest averages of 55 and 56 respectively, while others such as Ian Chappell and Gordon Greenidge only averaged in the 30s. And this was against bowling attacks including Lillee, Andy Roberts, Joel Garner and Michael Holding.

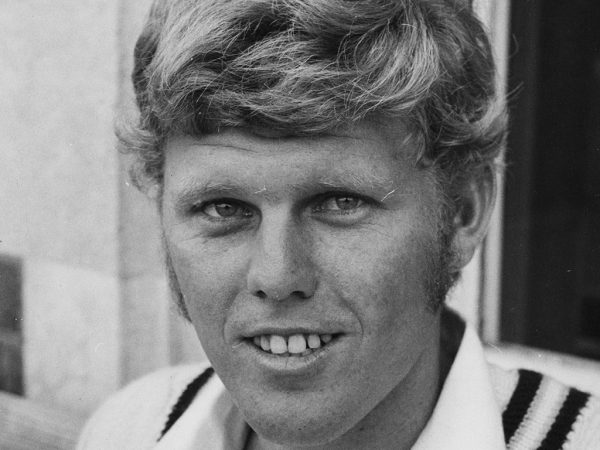

He was also rather hunky.

The author did his research well, with plenty of willing interviewees adding colour and context to stories. Other cricketers of the era also turn up in supporting roles, e.g. Roy Gilchrist, who we learn was sent home from a tour to India for bowling beamers from 18 yards in a Test, and who later played in the Lancashire League where he hit a batsman over the head with a stump.

The book also discusses South African cricket during the country’s exile from international sport. Clearly there were very good players at this time whose true greatness couldn’t be tested. However Richards and Murtagh are disappointingly patronising in saying a Natal side from the 70s “would have knocked the stuffing out of the Zimbabwe and Bangladesh sides of today.” Murtagh even lists respective XIs and asks if the reader has heard of any of them. Yes Andrew, we have indeed heard of Shakib Al Hasan and Mushfiqur Rahim. We also spotted a few errors in the book, for example in a section on players’ earnings, apparently Graham Hick’s benefit year raised £300,000 in 1980 – the year he turned 14.

The book’s title(s) are all apposite. He probably was a genius lost to Test cricket. This is his story. And as Murtagh quotes Benjamin Franklin, “Hide not your talents; for use they were made. What’s a sundial in the shade?” What would his Test career have been if he had played for 10 years? Truly one of the great what ifs.

No Comments

Post a Comment