A gradual but inevitable descent into cricket-based loathing and bile.

Positional Batting Average: What Difference Does It Make?

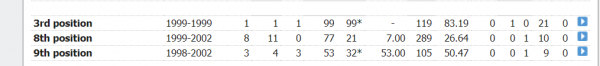

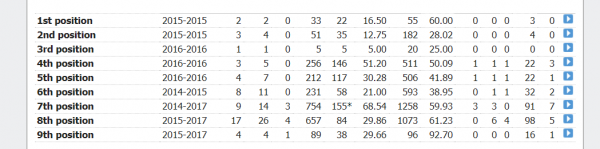

When devising potential England line-ups, one of the key questions is where should so-and-so bat? Others may prefer to rephrase the question, and ask who should bat at x-and-y? The most obvious solution in both cases is to look at batting averages on a position-by-position basis. This is something that even Sky Sports with their gigantic budget and fancy graphics regularly do, using positional batting average as proof that Alex Tudor should always bat at no. nine, because he is more than seven times better than when he bats at no. eight. Of course, had he been dismissed in that famous stint as nightwatchman, he’d have ended up batting at no. three forever.

Fact.

Obviously, this is simplifying things to an excessive degree, but people talk about Moeen Ali’s record at no. eight compared with no. seven (and indeed nos. one to six and nine) as if his average is the only variable that matters. When it clearly isn’t so straightforward.

Fact.

We have often devised alternative methods of assessing batsmanship. As long ago as 2011, we were praising Jonathan Trott for his ability to score hundreds from no. three regardless of the score at which he came to the wicket, whilst we also wrote about the role of the no. three here. In the latter case, we concluded that seldom do no. threes make good openers. The pertinence of this discussion is evident, now that England travel to Australia with an unproven opener in the shape of Mark Stoneman, and an apparent commitment to have James Vince bat at no. three.

The question that must be begged, is whether Joe Root should bat at three or at four. He wants to bat at second drop, and plenty of people are happy to endorse this. After all, his average (54.38) is nine runs per innings better than when he is first man in (45.33). Case closed. Notwithstanding that he averages 73.12 at five, so he should actually be demoted one place.

With Root cementing himself in at four, Vince is expected to fill the gap at three. Which would be fine if it wasn’t for the fact that his batting average at nos. four (19.75) and five (18.00) suggest he is as well suited for that role as Jeremy Hunt is suited for a role as a high-ranking member of the Cabinet. After all, the argument is based entirely on averages, isn’t it?

Fact.

What these batting averages don’t give us is any context. Root batted at three in the Ashes down under (before he was dropped), at home in 2016 and then in the substandard tour of the subcontinent last autumn. His knocks at no. four also come in different arenas, including the UAE and South Africa, but predominantly at home. As his average at home is just shy of 60, and away a tad over 46, this too doesn’t really tell us much, given the sheer number of variables to take into account.

In identifying whereabouts in the batting order one should be placed, our view is that all players need to be considered together. In which case, placing Root at no. four (in itself, not a bad decision) is nonsensical if it means Vince bats at no. three. To draw this to a conclusion, we have listed below Root’s Test centuries. If he only scored centuries when the team was finding it easy to score runs – for example coming in to bat at 200/2 – and always struggled when batting against a newish ball, then batting in the middle order would make some sense (assuming there was an appropriate candidate to come in ahead of him).

Root has scored 13 Test centuries (and many more half-centuries). Excluding when he opened the batting and scored 180, he began seven of these hundreds before the scoreboard had reached 50.

- 254 vs Pakistan (25/1, 7th over)

- 200 vs Sri Lanka (74/3, 19th over)

- 190 vs South Africa (17/2, 6th over)

- 182 vs West Indies (164/3, 67th over)

- 180 vs Australia (0/0)

- 154 vs India (154/3, 54th over)

- 149 vs India (201/3, 63rd over)

- 136 vs West Indies (39/2, 8th over)

- 134 vs Australia (43/3, 15th over)

- 130 vs Australia (34/2, 14th over)

- 124 vs India (47/1, 16th over)

- 110 vs South Africa (22/2, 11th over)

- 104 vs New Zealand (67/3, 26th over)

This may not be unequivocal, but it shows that he is capable of batting in different situations. Of course, this doesn’t take into account other issues like the result of the match, his strike rate or how others fared lower down the order. However, for us, it is sufficient evidence to force him to bat front and central in the team’s key spot, and let the lesser batsmen – for that is what they are – battle it out for the rest of the positions.

No Comments

Post a Comment