A gradual but inevitable descent into cricket-based loathing and bile.

Whatever Happened To The Unlikely Lads (International Edition)? #64: Trent Copeland

We have written at length about the Sheffield Shield before. Usually in articles that attract about as much attention as your average Shield fixture. For the Shield exists inside its own little bubble, which contains only the players, a few diehard supporters and maybe a national selector who accidentally stumbled into the ground by mistake and can’t find their way back out again quickly enough.

But every now and then the Shield blossoms into something else entirely. Sure, nobody still watches the thing, but people start talking about it. The beginning of this Shield season was just one such example. The looming Ashes and the return of big name players grabbed the media’s attention. Thus it was all the more amusing when, despite the endless debate about wicket-keepers, all-rounders, and Mitchell Starc’s remarkable efficiency in cleaning up the tail (truly the three-ply toilet paper of international cricket) the plaudits were instead stolen by one:

#64: Trent Aaron Copeland

Copeland belongs to a select group of Australian bowlers, amongst the likes of Michael Hogan and Clint McKay, who might be considered journeymen. Quicks remarkable not so much for their pace, but their wicket-taking prowess, longevity and almost universally daggy haircuts. It’s almost as though they are slavishly trying to model themselves on Glenn McGrath in hopes of emulating his success.

In truth, McGrath’s unique powers came from devouring the souls of butchered African wildlife.

As models go they are good but not quite perfect, as they usually lack McGrath’s accuracy or his impeccable sense of timing. McGrath peaked at the right time and the right place (i.e. with New South Wales) to ensure a long stint in the Australian Test setup. This is something those others have lacked, and aside for a single cap for McKay (a topic for another article), only Copeland has earned a baggy green. Which, again, is almost certainly on account of his playing for New South Wales.

Copeland made his Test debut in Sri Lanka in 2011. A series in which Michael Clarke was also making his debut as Test captain. It was a series which Australia also won. Their last series win in Asia to be exact. Across the three Tests, Copeland contributed six wickets at 37 runs apiece. Not great, but not bad for subcontinental pitches either. And yet something was clearly amiss and his days as a Test cricketer, even at this early stage, were evidently marked.

The problem was that Copeland was slow. Not even medium fast slow, but rather nearly medium pacer slow. Clarke, as the new captain, hoping to instil an aggressive mindset in his charges, clearly wasn’t keen on having an economical packhorse in his ranks when he could have an out and out strike bowler instead. Rumours circulated that Clarke wasn’t happy at all with the selectors having dumped Copeland on him and for the next series, in South Africa, Copeland found himself replaced by Peter Siddle. Another workhorse to be sure, but a vastly more aggressive variant.

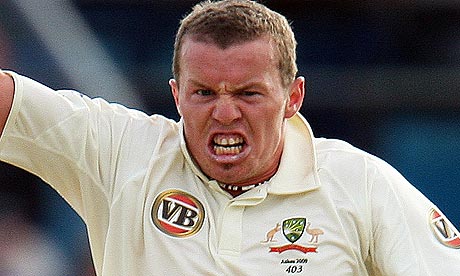

Siddle courteously asks the umpire for his hat back at the end of the over.

So ended Copeland’s brief Test career. A month of dutiful toil on unhelpful subcontinent pitches was rewarded with a swift boot up the arse, back to the state leagues where he belonged, and from which he will never again re-emerge. It’s for this reason that Copeland’s performance in the first Shield round was so hilarious. The press coverage beforehand was hyperbolic. Starc! Cummins! Hazlewood! And yet here was daggy Copeland, running through South Australia and denying the limelight to Cricket Australia’s darlings.

You could almost sense the fury of the selectors towards this pathetic relic who was denying the current Australian pace attack a proper hit out. Was it any surprise when Copeland was subsequently dropped for the next game? No more surprising than Cowan being dropped was. Which just makes it all the more satisfying to see Copeland, on his return, cheaply remove Matt Renshaw. Another giant middle finger to the Australian selectors who no doubt would love to send Copeland to the knackery by now.

Under Pat Howard’s leadership, Cricket Australia reached new heights of efficiency and inclusiveness.

Thus Copeland’s journey is a cautionary tale to other bowlers who might hope to follow in McGrath’s footsteps. Australia’s obsession with pace was entrenched with Clarke’s elevation to captaincy, and Copeland became but its first sacrificial victim. Players like Chadd Sayers can look forward to similar careers, and it would be advisable for them to follow instead the path of bowlers like Hogan and McKay to county cricket, where their ability is far more highly valued.

Meanwhile, for Copeland there is no limelight, no Big Bash, only the Sheffield Shield (when the big boys aren’t around) and the dubious recognition offered by the sad, pathetic, losers who actually pay any attention to that competition. People like us.

No Comments

Post a Comment