A gradual but inevitable descent into cricket-based loathing and bile.

Passengers And The Ramprakash Factor

When talking about a player’s worth in the grand scheme of things, it’s traditional to fall back on talking about their averages. Over the course of a career they’re a pretty decent reflection of how good a player was. But, as with all these things, the devil is in the detail.

In previous Scorers’ Notes columns we’ve looked at ideas such as the rolling average as ways of getting a bit more information from a player’s average. Here we’re going to consider another concept: the passenger. In order to define what we mean by a passenger, we need to have a bit of a think about one specific question.

In a standard Test series, what would be considered a ‘reasonable’ average for a batsman?

Of course, every batsman would love to average somewhere around 330 in each and every series, but that’s rather unlikely. Still, remember that number – there’ll be a callback to it later on. If we said that averaging 50 represented a very good series then there’s unlikely to be much disagreement. Especially because we moderate the comments, so any nay-sayers would just be ignored as we strode on, rewriting history exactly as we wanted it, in a distinctly Stalin-esque manner. If those commenting were really unlucky they’d be sent to a penal labour camp. Having said that, there’s probably no internet there and we can’t really afford to lose the hits.

But where do we draw the line between a poor series and an average one? If we were one of those shockingly dull cricket websites that are obsessed with statistics and statistical methods we could spend months coming up with formulae using weightings and coefficients that take into account pitch conditions, bowling standards and the fact that Sachin clearly doesn’t give a fuck about the team when personal glory is at stake. It figures that we’d then have to spend months defending our methodology against attacks from even nerdier people, those who are too busy finding holes in other people’s analysis to do their own.

Luckily we’re not one of those websites. We get to talk to girls sometimes, for a start. So instead of dicking about with maths we’ll use our experience and intuition to come up with a definition of the line between a reasonable series and a poor one. Like all good maths things, it’ll need a fancy name. Ladies and gentlemen, may we introduce to you:

The Ramprakash Factor

If there was such a thing as the 51allout dictionary, under the word ‘mediocre’ you’d probably find this picture:

Mark Ramprakash’s Test career was the dictionary definition of unfulfilled potential. Time after time he got in, played a couple of attractive shots and then got out. Thinking about it, he might have been doing it purely to save housewives from fainting at the sight of him reaching 30. Or he might have been a bit rubbish – we talked about him quite a lot here.

Anyway, let’s take Mark Ramprakash’s very first disappointing series (in 1991 against the West Indies, which we also talked about in some depth here). Batting at number five he made scores of 27, 27, 24, 13, 21, 29, 25, 25 and 19. Or, more succinctly, 210 runs at 23.33. Like we said, disappointing stuff. By the end of his disappointing Test career Ramprakash had only managed to raise his average to the giddy heights of 27.32.

Common sense tells us that Ramprakash therefore trod the fine line between between ‘poor’ and ‘just about acceptable’ throughout his career. So if we take his final average and his first series average and, er, take the average we get a smidgen over 25.

Therefore, the line between a poor series and a just about acceptable one falls at exactly 25. Now that is scientific fact – there’s no real evidence for it – but it is scientific fact.

Passengers

To get back on topic, we can use the Ramprakash Factor to look at how often in a player’s career they didn’t pull their weight in a series. Yes, Ricky Ponting has done well over the years (and has a shiny Test average of 53.44 to show for it) but that can’t hide the fact that he stunk up the 2010/11 Ashes like a skunk recovering from a heavy night on the cheap gin. By averaging just 16.14 he fell well below the Ramprakash Factor and was therefore nothing more than a passenger in his team.

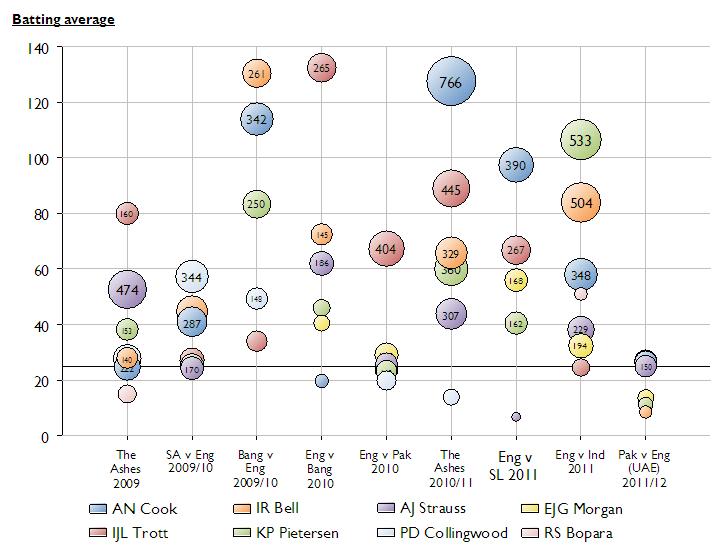

Our next step is to look at the number of instances of players being passengers.To get a bit of contemporary focus, let’s look at England’s Test series over the last couple of years. For the batsmen only, we’re looking at batting average (the y axis) and runs scored (the bubble size, or z axis as nerds might call it):

We’ve colour-coded each batsman to hopefully make it a little clearer. We should also point out that for the Sri Lanka in England series in 2011 Ian Bell averaged 331 – we told you there’d be a callback – but we had to cut that off the top of the chart. Ian Bell was amazing back then. Nowadays he’s about as prolific as Fernando Torres.

The key thing is that we’ve drawn a line across at the magic number of 25. Anything that falls below that is a passenger. In the case of the most recent series against Pakistan, the whole top order were basically passengers – Cook and Trott escape with mighty averages of just below 27. Working backwards from that there was Trott against India, Strauss against Sri Lanka, Collingwood in the Ashes, Collingwood and Pietersen for the home series against Pakistan, Cook against Bangladesh, Strauss in South Africa and Cook and Bopara in the 2009 Ashes.

With all these passengers in the side it’s amazing that England actually won all these series (bar the draw in South Africa and the spanking in the UAE). Perhaps that’s the difference between a good side and a great side – the latter has no passengers (either with bat or ball).

Of course, having defined a passenger we can now apply that to a player’s career and see what proportion of series they have passengered in (it’s definitely a word – it’s in the 51allout dictionary). Of particular interest here are Eoin Morgan and Ravi Bopara. Both have taken part in five Test series and in terms of straight batting average Bopara has the edge (34.56 vs. 30.43). While neither are exactly great, a difference of over four runs is fairly significant.

However, in his five series Morgan has only been a passenger once – the most recent series in the UAE. Prior to that he’s been in or above that ‘just about acceptable’ band that frustrates everyone – coaches and spectators – so much. Bopara, on the other hand, has twice been a passenger – the 2009 Ashes and England’s previous Test tour of Sri Lanka. And that tells us something about the man, specifically that when’s he’s rubbish, he’s consistently awful. When he’s good, he’s better than Morgan (hence that higher overall average) but that’s hardly a ringing endorsement as he prepares to come back into the side.

Of course, a lot of players have difficult starts to their Test career before settling in – Hashim Amla being a prime example. There’s nothing to say that Ravi Bopara won’t come good this time around.

Apart from us: Ravi Bopara won’t come good this time around.

So who is the passengerest (again, see the 51allout dictionary) of the England top order?

- Ravi Bopara: 2/5 series = 40%

- Ian Bell: 6/23 = 26.1% (one of this six is his single Test vs. West Indies away in 2009 that gave us our name)

- Paul Collingwood: 5/21 = 23.8% (although one of those five is his single match in the 2005 Ashes)

- Andrew Strauss: 6/26 = 23.1% (includes one series where he averaged exactly 25, the awkward bugger)

- Eoin Morgan: 1/5 = 20%

- Alastair Cook: 3/22 = 13.6%

- Kevin Pietersen: 3/24 = 12.5%

- Jonathan Trott: 1/9 = 11.1%

What does this tell us? Ian Bell’s second place on the list is a testament to a remarkably patch Test career. At the other end Trott’s consistency is obvious – even when he’s not at his best he still scores ugly, ugly runs. And even Alastair Cook and Kevin Pietersen have struggled at times in their otherwise massively prolific careers. Maybe Test cricket isn’t actually that easy after all. Just ask Mark Ramprakash.

No Comments

Post a Comment