A gradual but inevitable descent into cricket-based loathing and bile.

Whatever Happened To The Unlikely Lads (International Edition)? #12: Vinod Kambli

By Arjun Miglani

At the end of his career, his Test batting average was 51.64. Unfortunately, said Test career ended after 23 games, at the age of just 24. So what went wrong with

#12: Vinod Ganpat Kambli

Kambli went to school with some guy named Sachin Tendulkar and their unbeaten partnership of 664 (then a record) in a school game is the stuff of legend. Tendulkar went on to make his Test debut at the age of 16 (a nice age to face Wasim Akram and Waqar Younis), but Kambli had to wait three more years to get his chance. His first two innings didn’t produce much but after scoring a fifty in his third his next three innings suggested that, just as he had been during their childhood, Kambli was every bit Tendulkar’s equal on the international stage.

It started with a murderous 224 against England, which saw the likes of Chris Lewis, Phillip DeFreitas and Phil Tufnell carted all over the Wankhede stadium with reckless abandon (although had DeFreitas not spilled a fairly easy chance in the outfield, this article might never have been written). Raising his bat as he guided the ball down to third man to reach 200, Kambli had scored a double century before Tendulkar had, in just his second Test. Just to rub it in, he scored 227 in his next innings against Zimbabwe. He then scored two hundreds in his next three innings. Sachin who?

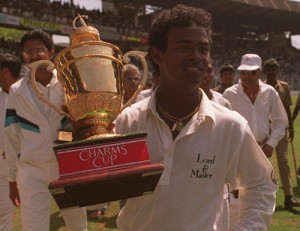

Kambli shows off the trophy he received for becoming an Unlikely Lad. Ian Salisbury's sadly came back to us, marked 'Return To Sender'.

Two more fifties followed soon after, but then came one of the great declines. Kambli failed to reach 50 in his next ten innings, including three ducks, and that was the end of his Test career. Sure, that’s a bad run, but worthy of dropping an undeniably gifted player forever? Surely there were other factors involved.

Kambli’s ODI average was only 32.59 (although it did contain an over in which he utterly humiliated Shane Warne by smashing him for 22 with disdain), but it is from this arena that the most enduring and, frankly, sad image of him persists. India were playing Sri Lanka in the 1996 World Cup semi-final at a packed Eden Gardens, and yours truly was in attendance. India put the Sri Lankans in to bat (more on this later) and we all sat in trepidation at the thrashing tournament heroes Sanath Jayasuriya and Romesh Kaluwitharana were about to hand out (on a vaguely related note, Venkatesh Prasad’s dismissal of Aamir Sohail from the quarter-final is essential viewing…but I digress). Then, within minutes, we were in the World Cup final. So we thought, anyway. Jayasuriya and Kaluwitharana had both holed out to third man and, at 1/2, there was surely no way back for the Sri Lankans.

Ultimately, they reached 250, thanks mainly to a gem of an innings from Aravinda de Silva. Still, it shouldn’t have been a problem, and it didn’t look like it would be as India closed in on 100 with just one wicket down and Tendulkar in full flow. And then…well, the mother of all collapses. Before anyone knew what had hit them (a plastic bottle, probably), the hosts were 121/8, their World Cup dreams in tatters. The ball was suddenly turning square, but the dismissals were tame too. The crowd had had enough and the playing field was pelted with Pepsi bottles while seats were burned. Inevitably, the match was abandoned and eventually awarded to Sri Lanka. In all this, Kambli had stood at one end, watching his team-mates come and go. It was too much for him to bear, and he left the field crying. While he did play a few games after this, it was, for all intents and purposes, the end of his career.

Last year, 15 years after the event, Kambli brandished allegations of match-fixing against some of his team-mates. His main charges were that bowling first was a ludicrous decision, that batsmen threw their wickets away and that people were crying “crocodile tears” in the dressing room.

While these allegations caused a media storm initially, they have largely been forgotten. Whether they are true or not is a matter for another time. What the incident confirmed, though, was that Kambli has always been an outsider in Indian cricket, or at least felt like one. Just like his batting, Kambli was a flashy character. He liked earrings, changing his hairstyle, and generally living large. Unfortunately for him, it was the early 90s, not 2012. Modern Indian culture is more accepting of such things, as evidenced by the presence of Virat Kohli et al in the national team.

Of course, Kambli has to take a fair share of the blame. No matter how mistreated he felt, had he kept on scoring runs, no-one would have had the balls to drop him. He had a weakness against the short ball (a national disease it seems), but this alone cannot possibly explain the drastic drop in runs. Most people don’t perform when they don’t feel wanted, and it seems fair to say that Kambli, whether justifiably or not, felt increasingly victimised, or quite simply didn’t fit in.

Of course, no-one really knows why this incredible talent regressed in such spectacular fashion. This article was never going to answer that. Cool people like myself, though, are drawn to “flawed geniuses” like Kambli. Not for me your Athertons, your Cooks, or even your Tendulkars, players who get the job done and never hit the headlines for the wrong reasons.

Kambli, despite being far, far more talented, has always seemed like one of us. He lives in our world, the world where, every now and then, you f**k up. Or every day, if you’re a 51allout writer.

As time goes by, people will gradually forget who Vinod Kambli was, and that is largely his fault. Ultimately, in the words of the Beach Boys, he just wasn’t made for those times.

No Comments

Post a Comment