A gradual but inevitable descent into cricket-based loathing and bile.

Baggy Green And Gold All Over: Just Who Does The Australian Test Team Represent?

The question of exactly whom the Australian Test team represents is one that has the bean counters at both Cricket Australia and Channel Nine in a state of great agitation. For the face of today’s Australian side bears little resemblance to the state of contemporary Australian culture. Instead, the current team is a throwback to the Anglo-Saxon roots that can be considered the basis of ‘Old Australia’. With the increasingly multicultural nature of ‘New Australian’ society, it is a question of no little importance, especially to those with a financial investment in the sport’s continuing success. The oft repeated cliché is that the position of Australian Test captain is the most important job in the country, relegating the Prime Minister into second place. While we’re not big on hyperbole (or research), we can only imagine that whilst the majority of Australians would recognise Michael Clarke, far fewer could claim to recognise the source of his fame. Beyond the celebrity girlfriends of course.

Arguments of this nature always tend to elicit a fair bit of controversy and so, just this once, we’ll begin on a factual basis*. Historically, the greatest source of immigrants into Australia have been from the United Kingdom and New Zealand. And while some have attempted to argue the contrary, it’s a trend that has continued right up to the current day. Today the single largest contributor of immigrants to Australia remains the United Kingdom (without naming names, one of whom writes for this very site), while New Zealand is also hanging on grimly. However, over the past ten years the contribution from both of these countries has declined in terms of the proportion of overall immigrants. Of particular interest, therefore, are those countries that now follow both the UK and New Zealand in the proportion of immigrant arrivals in Australia each year. Whilst traditionally these spots were filled by fellow Commonwealth states, nations such as China and the Philippines now loom large.

This line of argument is not intended to be alarmist, but instead aims merely to indicate that behind these figures the reality is that contemporary Australian society is a far different beast now compared to the 70’s and 80’s, and if current trends continue will only evolve further. This is a statement that may appear somewhat exaggerated to those whose concept of ‘Australian identity’ is based on the bronzed Aussie stereotype. The truth, however, is that the image that Australia attempts to sell of itself, largely in the interests of promoting tourism, has never been an accurate representation of reality. Contemporary Australian identity is a far more complicated and multi-faceted entity than the simplistic images that the media likes to employ.

You might be wondering what this discussion is doing on a cricket site. The answer is because this is an issue of almost supreme importance to the sports administrators in Australia. Whilst Americans may claim to have the most competitive sporting landscape in the world, we would suggest they (those with passports that is) actually spend some time in the saturated marketplace that exists within Australia. Four different football codes plus tennis, golf, and untold other sports all compete in an often ruthless manner for both media patronage and the public’s attention. In the centre sits cricket, nominally the national sport and undisputed ruler of the summer months. In truth though, cricket’s crown has been slipping for some time. Dwindling attendances at ODI’s, with a similar dip in television audiences, tells the tale. Frequent surveys on the subject reveal that in terms of popularity cricket consistently trails in the wake of both tennis and swimming, whilst in regards to participation at junior levels it also falls behind all the footballing codes bar rugby.

Whilst the cultural and sporting landscape of Australia has changed dramatically over recent years, the public face of Australian cricket has barely shifted one iota. If you compare the Australian Test team to other national sporting sides, such as the football or rugby (union or league) teams, the difference is obvious. Whilst these other sides, football in particular, can claim to represent a comparatively broad proportion of contemporary Australian society, the cricket team is drawn from an increasingly narrow spectrum. It’s not an issue that you find, for example, within the English cricket team, where, whilst it may be somewhat disproportionate in its representation of the emigree South African community in the UK, the squad can claim to be a broad representation of contemporary British society as a whole. The Australian cricket team, however, is almost an entirely Anglo-Saxon affair. Whilst there have been some representatives from outside of this group in the recent past, with Lenny Pascoe, Jason Gillespie, and Andrew Symonds all springing to mind, the at times galling media euphoria that surrounded Usman Khawaja’s elevation in 2011 is evidence of how desperate the sport is to embrace diverse cultures within its national team.

It might seem somewhat disingenuous to point it out, but the simple fact is that the homogeneous face of Australian cricket seriously hampers its appeal to ethnic communities. A case in point is the fact that immigrants undertaking Australian citizenship tests were, until recently, asked about Bradman’s Test batting average, since apparently knowing that figure defined the typical Aussie identity. Research by the government revealed, however, that most applicants simply noted down 99.94 from memory, as they are actively encouraged to study the questions beforehand, without knowing either who Bradman was, or even what Test cricket is. Cricket Australia is certainly not unaware of the ramifications of this issue. In a recent revealing interview Cricket Australia CEO James Sutherland praised the success of the inaugural Big Bash competition as the great success story of the past Australian summer. At the heart of Sutherland’s praise was the belief that the competition provides a unique opportunity to introduce the sport to new audiences. In the interview Sutherland outlined that Cricket Australia was determined to “keep in touch with today’s Australia”, and that the old approach of cricket being skewed towards the interests of “the male Anglo” had to come to an end.

Such stark statements from an administrator may seem surprising but in fact merely reflect the pressure the game is currently under. The simplest expression of this pressure can be found in terms of revenue, and whilst cricket in Australia is far from bankrupt, it isn’t exactly in the rudest of health either. The recent news that Vodafone is set to end its sponsorship of the Test team certainly doesn’t help matters. Nor does the recently concluded stand-off with the Australian Cricketers Association. The players themselves seem to understand what is at stake, with Michael Clarke, in commenting on the negotiations, claiming the players only wanted what was ‘fair’, with their main interest being for “the game to continue to be the number one sport in this country.” While three Ashes series in four years will definitely help fill Cricket Australia’s coffers, it cannot rely purely on the sport’s premier contest to consistently cover its expenses. Things, however, are even tighter at Channel Nine, whose interest in the health of the game extends back to the days of Kerry Packer’s World Series.

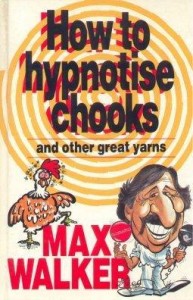

Its understandable that the cricket coverage found on Channel Nine can appear barbaric, particularly to those used to the more subdued affair offered in England. Frequent cries of “did you see that!”, “shot!”, “that was huge!”, and “$595 plus postage and packing!” effectively drown out all else, including the sound of Richie Benaud quietly weeping in the corner. The cause for all this tedious hyperbole, however, is Channel Nine’s desperation to promote the sport as a ‘product’ to those who are unfamiliar with it. Channel Nine has been, to put it simply, in deep financial poo for quite some time now, and with cricket its main staple in the summer months it is desperate to attract as large an audience as possible. It also explains Channel Nine’s push to increase the number of T20 Internationals played each summer, which are rating winners for the broadcaster. Whilst the purists (including this author it must be said) flee to the more gentile surroundings offered by the ABC radio broadcast, Channel Nine’s approach is at least understandable. A coverage primarily aimed at satisfying the interests of cricket purists would do nothing to expand its reach into communities who have not been brought up on stories of Doug Walters’ drinking feats and Max Walker’s extensive back library of classic works.

Whilst the discussion above may appear novel or reactionary to some readers, in truth this article could have been written at any point over the past 40 or 50 years. Ever since the final dissolution of the White Australia Policy in 1973 Australian cricket has struggled to define its identity in regards to a rapidly changing society. The disaster that was 2010/11 has brought these questions back to the fore. Australian cricket has been through crises before, most recently in the mid 80’s, but none perhaps as critical as this. Whilst it is not a matter of considering the death of cricket in Australia, serious and pertinent concerns have been raised as to whether the sport possesses the resources to rebuild to the extent that it will be able to compete internationally, at least in the consistent manner in which the Australian public has become accustomed. Whilst the fare on the field has been of a questionable quality in recent years, the intrigue provided by off the pitch issues nearly makes up for it. Australian cricket is certainly living in interesting times.

*All the data here is sourced from http://www.immi.gov.au/media/publications/statistics/popflows2010-11/pop-flows-chapter4.pdf so if you happen to disagree with any of it, take it up with Julia Gillard. We are sure she would just love to hear from you. Also feel free to ask her about the Carbon Tax. She loves that shit.

1 Comment

Post a Comment

1

Ben Smith

02 Jul 2012 19:21

Fascinating stuff chaps.