A gradual but inevitable descent into cricket-based loathing and bile.

Whatever Happened To The Unlikely Lads (International Edition)? #59: Shane Watson

You know you are dealing with a very special player indeed when you can’t decide just what your favourite way to mock him is. Personally we like to dwell upon Watto’s hilariously limited contributions in winning sides over the years, such as the meagre role he played in the Sydney Thunder’s recent Big Bash success. Of course, the outlier is the 2008 IPL season, where Watto, the modern cricketer made manifest, strode onto the stage promising greatness the likes of which the world had never seen before. And then subsequently delivered the square-root of bugger all over a career of consistent mediocrity. Watto was the one man you could rely upon to fail when it really mattered, and to stand up when it didn’t matter at all. Instead of becoming the ultimate modern player, he became the ultimate passenger. Never in the course of human history has so much been owed by one man to so many, as by

#59: Shane Robert Watson

Of course, it would be unfair to say Watto never accomplished anything. He had his moments. In a career that long you are bound to have a few. But they were so few and fleeting it’s difficult to remember many of them off-hand. Take his ‘contribution’ to Australia’s 2015 World Cup success, where his greatest accomplishment was in not failing. Exactly. Although he certainly tried his best in the quarter-final, only for the Pakistani fieldsmen to make a point of insisting on dropping him.

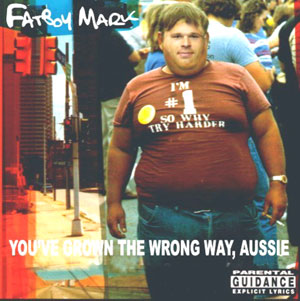

Watto in standard ‘undeservedly stepping into the limelight’ pose.

Then there is his much mocked tally of four Test centuries (compared to Jacque Kallis’, a player Watson was much compared to in his earlier years, tally of 45). Of those four, only one, his century in Mohali in the first Test of the 2010 tour of India, could be said to be truly match defining. The rest were either in the second innings when Australia already held a commanding position, or came at the expense of Simon Kerrigan. In a dead rubber.

That 2013 Ashes series really was the nadir of Watson’s career. He should have bossed it, really. He went into it after having absolutely plundered county bowling attacks in the lead-up games. He was one of the few senior players in the team, and one of Australia’s only real hopes of making a contest out of the series. Yet take out that meaningless ton in the last Test and he averaged 26 for the series, with one half century in nine innings. It was classic Watto. Much like Mark Viduka made a career of doing, he did as little as possible when it actually mattered, and only turned up when his own position in the team looked to be under threat.

Viduka’s career certainly took a few odd twists along the way.

We could waffle on about classic Watto moments all day, everybody remembers them. Falling over bowling his first ball in Test cricket; the LBWs; fleeing the Australian camp during the 2013 tour of India, only to return and be made captain for the last Test, in which he had Glen Maxwell open both the batting and bowling; the frequency with which he either ran himself or his partners out; the utter disdain he showed whenever Michael Clarke asked him to roll his arm over for an over or two; his attempts at sledging which seemed to always backfire hilariously; his stupid haircut; his stupid face; his whole stupid, fucking pointless career.

You get the drift.

But we don’t hate Watto (don’t we? – Ed). How could we hate a man who has brought so much enjoyment into our lives? The usual plaudits accompanied the news of his retirement, and we would like to add ours too. International cricket will be poorer for Watson’s absence. Admittedly it will probably be of a higher standard, but still a lot less fun to watch. Australia look intent on replacing him with Mitchell Marsh, a measure which promises to be about as successful as the new Ghostbusters movie. In that it will do all the same sorts of things that you expected from the previous version, but just be far, far less funny in doing so.

And of course, Watto will not retire from our gaze completely. He will still be there in the IPL and the Big Bash, moving at a glacial pace in the field, whilst wearing that constant look of befuddlement whenever an attempt at a slog sweep only ends up with the ball splattering his stumps. You know the one we are talking about.

That’s the one.

It’s that look of confusion that will be our abiding memory of Watto. It’s as if he didn’t understand this game of cricket at all. He certainly didn’t understand how DRS works. But he constantly seemed perplexed as to why people seemed to be picking on him, why his captain kept asking him to bowl, or why scoring centuries was so hard when everyone around him seemed to make it look so easy. That Steven Peter Devereux Smith scored as many in four Tests against India in 2014 as Watto had in his entire career seemed to baffle him. How could such a thing be possible? Even basic maths seemed beyond him.

Watto was like an innocent child who wandered into international cricket on the strength of his ability to hit the ball a really long distance. That cricket would ask more of him than that seemed to come as complete shock, and one that he never seemed to fully recover from. So whilst we hate Watto (that’s better – Ed), and everything he stands for, it was in his ultimately doomed journey to try to come to terms with the world which he found himself thrust into, we came to love him too.

God bless you Watto, and thank you. For everything.

No Comments

Post a Comment