A gradual but inevitable descent into cricket-based loathing and bile.

Hansie Cronje: Ten Years On

By Anthony K

Today marks the tenth anniversary of the death of the former South African cricket captain Hansie Cronje. Many UK readers will have heard Mark Chapman’s excellent documentary for BBC Radio 5 Live, broadcast this week to mark the occasion. No player’s tale is truly worth telling if it fails to go beyond its immediate sporting context, but few can have such scope as Cronje’s, touching as it does on religion, race, politics and deep psychological questions of shared memory, repentance, forgiveness and how a society copes with a fallen idol.

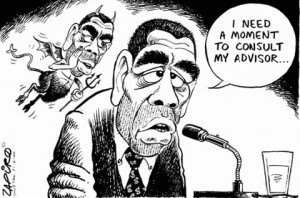

Cronje was appointed by Nelson Mandela as one of the twin sporting ambassadors, with Francois Pienaar, who would help to heal internal rifts in South African sport and society, presenting an image of decency abroad for a nation which badly needed to be rehabilitated in the international community. The seeming embodiment of what white South Africa, and especially the Afrikaaner community from which he sprung, saw as its core values, Cronje appeared the very model of humility, morality and universality. A devout Christian, with an unblemished public persona, some would argue that if Hansie Cronje had not existed, they would have had to invent him. The problem was that they had.

For, as we all now know, Cronje was a flawed character with a lethal addiction to power and money. That his human failings should have come as such a revelation is largely the point of his story. Yes, the implications for cricket are serious and have been well-documented, but it is his fall, abortive rise and the subsequent battle for his legacy that make his story truly fascinating.

There has been optimistic talk about how Cronje was forgiven so readily by so many because South Africa is both a very religious country and because repentance, reconciliation and forgiveness had been thrust into the forefront of South African society by the dismantling of Apartheid and the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which provided something of a blueprint for the King Commission, before which Cronje either came clean, or confirmed everything that could easily be found out from other sources, depending on your point of view. The Cronje story might invite the question as to whether the community from which he came might have a pressing psychological need for the idea of forgiveness to become the new orthodoxy. One is forced also to acknowledge that many of those calling for his rehabilitation never really accepted that he had done anything wrong.

Cronje has been described as one of the most tragic figures in South African history, a claim which this writer would not want to try out in the Biko household. Others see him as exposing the moral corruption at the heart of his community, which projected Christian values so strongly, whilst inflicting Apartheid on its countrymen.

Distance, chronological and geographical, lends perspective. The truth lies between these points and yet is wider than both. We need to stop transferring our hopes as nations onto our fallible young sportsmen. They cannot bear the burden of assuaging our shared unease at past misdeeds any more than they can win every match or series and we might ask whether it is of any value that our societies still infer absolutes, good or bad, from a man’s religion or lack thereof. South Africa has come a long way in a short time. Fully digesting these lessons will help propel that country further still on its remarkable journey.

2 Comments

Post a Comment

1

Matt H

03 Jun 2012 08:48

Excellent thoughts.

2

Ben Smith

01 Jun 2012 19:01

Brilliantly put.