A gradual but inevitable descent into cricket-based loathing and bile.

Cashing In Or Checking Out?

Debates in the 51allout bunker can go one of two ways. Sometimes they’re fascinating examinations of the nuances of cricket, examining the socio-political structure of both the modern game and the world in which it exists. Other times they’re basically just a bunch of drunken men hurling abuse at one another and waving their arms around, like Ricky Ponting debating the intricacies of Hot Spot with Aleem Dar.

As we watched Graeme Smith and Hashim Amla grind England into the Oval dirt last weekend, one of our debates broke out, luckily more in line with the former type than the latter. “Graeme Smith always does well against England”, the discussion began, “but there are loads of players who always do better against England than everyone else. Especially when England were rubbish, when people like Anil Kumble and Ajit Agarkar were queuing up to make hundreds, despite being unable to hold the bat the right way around against anybody else.”

This got our Scorers’ Notes juices flowing. Surely there must be a way to put some logic behind this and come up with a way to find out who tucked into England’s mediocre seam attacks more than anyone else? After five minutes of furiously scribbling on the back of a court summons (relating to unpaid Council Tax), the cry went out: we had a methodology. Plus apparently we were due in court yesterday.

We’re pretty sure that Council Tax is like the TV licence, and that they legally can’t make you pay it.

Here comes the science bit

Our logic is actually fairly simple, but it does require a little bit of basic maths. Hence, now might be a good time for those with a fear of numbers to nip off and get some more tonic water from the 24 hour garage.

Looking at a player’s career record, we calculate their batting average using this formula:

batting average = runs scored / number of dismissals

If we turn that around we can get runs scored as the focus:

runs scored = batting average * number of dismissals

Now, for the purposes of this analysis, we’ll just look at two variations of this formula. Firstly, we’ll look at each player’s performances specifically against England:

runs scored against England = batting average against England * number of dismissals against England

And then we’ll compare this against their career batting average i.e.:

potential runs scored against England = career batting average * number of dismissals against England

We can then assess the difference between the actual runs scored and the potential runs scored, and determine whether a player has done better or worse against England, and to what extent.

“I’m telling you, Wiles’ proof of the Taniyama–Shimura conjecture for semistable elliptic curves is wrong.”

As always, things are a lot better when (a) we have an actual example and (b) Steve Smith is involved. In the case of our favourite leg-spinning allrounder, so far in his Test career (as there’s obviously much more glory awaiting him in the future) he has 259 runs at 28.77. In his three games against England, as part of the 2010/11 Ashes, he made 159 runs at 31.80.

At a basic level, our Steve has done slightly better against England than in general. If we change his average against England to be 28.77 and do the calculation, that would have given him 143.85 potential runs. If we ignore the fact that 0.85 of a run would presumably leave him stood mid-pitch next to Shane Watson, we can work out that 159 – 143.85 = 15.15. Hence Steve Smith has helped himself to fifteen more runs against England than they really should have allowed. They were probably just taken in by his larrikin charms.

If we repeat this analysis for everyone in the history of Test Cricket we can create a league table of those that cashed in against England (i.e. those in credit), and those who were found out (those in debit).

Without further ado, let’s fire up some tables and have a look at the results:

Those who missed out against England

| Player | Career Batting Average | Career Batting Average vs England | Difference In Runs Scored |

|---|---|---|---|

| SM Gavaskar (India) | 51.12 | 38.20 | -840 |

| KC Sangakkara (SL) | 56.73 | 35.02 | -760 |

| KD Walters (Aus) | 48.26 | 35.37 | -722 |

| RN Harvey (Aus) | 48.41 | 38.34 | -634 |

| DG Bradman (Aus) | 99.94 | 89.78 | -569 |

| V Sehwag (India) | 50.79 | 27.04 | -499 |

| RT Ponting (Aus) | 52.75 | 44.21 | -478 |

| JH Kallis (SA) | 57.61 | 46.84 | -474 |

| GS Chappell (Aus) | 53.86 | 45.94 | -451 |

| VT Trumper (Aus) | 39.04 | 32.79 | -431 |

When we asked the bunker about who would be top of this particular table, the response was a resounding silence. Clearly, no-one had understood the question. After a brief interlude, in which we tried to explain what was going on using some puppets, followed by another interlude in which we waved a cricket bat about aggressively, the guesses finally began coming in. A few people guessed Jacques Kallis (although he was on the telly at that exact moment) and a few people picked Sangakkara, Sehwag and Ponting. One particularly bright (i.e. sober) spark even picked Doug Walters, a man described as ‘a knockabout who disliked training and going to bed early, and favoured drinking, smoking, solitaire and cribbage.’ Sadly his agent wouldn’t return any of our calls about Doug joining the 51allout team.

No-one picked Sunil Gavaskar though. It was a bit of an odd one, so much so that we had to double check our workings, in case we’d made a huge mistake. But if there was, we couldn’t find it. Gavaskar is remembered as a wonderful opening batsman, one that dragged an up-and-coming Indian side towards professionalism and the position they now occupy in world cricket (8th in the T20 rankings, behind Bangladesh and New Zealand). But his record against England was disappointing, as that average of just over 38 testifies. Despite reaching a half century on 20 occasions, he made just four hundreds against England in 67 innings, one of them a double hundred at the Oval in 1979 as India very nearly chased down 438 to win on the final afternoon.

Based on our maths, his 2,483 runs against England work out as 840 less than he probably should have made. Still, he can console himself with the fact that when we talk about him, it’s almost exclusively about his commentary, which plumbs Channel 9-esque depths of ineptitude.

We should also probably comment on Bradman, whose average of just 89.78 against England is surely proof that he was massively over-rated and belongs in the Peter Forrest/George Bailey/Marcus North class of batsmen.

Those who cashed in against England

| Player | Career Batting Average | Career Batting Average vs England | Difference In Runs Scored |

|---|---|---|---|

| IVA Richards (WI) | 50.23 | 62.36 | +558 |

| BC Lara (WI) | 52.88 | 62.14 | +444 |

| SR Waugh (Aus) | 51.06 | 58.18 | +392 |

| Saleem Malik (Pak) | 43.69 | 60.69 | +391 |

| ME Waugh (Aus) | 41.81 | 50.09 | +364 |

| AR Border (Aus) | 50.56 | 56.31 | +362 |

| N Kapil Dev (India) | 31.05 | 41.06 | +330 |

| DPMD Jayawardene (SL) | 50.43 | 59.94 | +323 |

| LG Rowe (WI) | 43.55 | 74.20 | +307 |

| GC Smith (SA) | 50.14 | 59.68 | +305 |

No surprise to see the two Waugh brothers in this table, as we seem to remember England spending most of the 90’s bowling (badly) at them. Mark Waugh’s inclusion here is probably the reason he made it to 128 Tests despite averaging in just the early 40’s. And yet it’s the two top names that truly grab the attention.

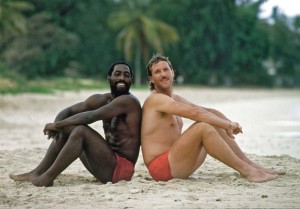

Brian Lara’s position here is no surprise, considering he made scores of 375 and 400* plus a further five hundreds and 11 half-centuries against England. He was, quite simply, the greatest batsman of his generation by a country mile and a producer of truly legendary innings. But even that superb record isn’t enough to grab top spot, with that going to one Viv Richards.

Richards’ role in history has long since been assured, but it mostly predates even the oldest members of the 51allout team. His very final series, in England in 1991, is on the very edge of stuff we can actually remember meaning the majority of his career for us is in scorecards, old clips and other people’s words. His record against England was astonishing and included 232 in his very first innings (at Trent Bridge), followed by 135 in the following Test (Old Trafford) and 291 at The Oval as England were smashed 3-0. With Richards in the side the West Indies won seven consecutive Test series against England (including the famous blackwash of 1984) before drawing the final one, the aforementioned epic of 1991. Plus he was, not to beat about the bush, pretty damn cool.

After winning inside two days the Somerset players had earned themselves a day at Weston-Super-Mare.

In conclusion

So what has this analysis taught us? Mainly it’s that analysis is all well and good, but it’s really just an excuse to reminisce about old stuff and play with our new table-drawing addin thingy. There will always be players who do well against some sides and not so well against others; that’s the nature of sport. But looking at the extreme examples has shown us some players who feasted on England’s dibbly-dobbly seamers as well as some who just couldn’t handle said dibbly-dobbling. And, more importantly, we’ve padded those players out to fill 1,400 words, thereby fulfilling our contractual requirement. And in the end, isn’t that what it’s all really about?

1 Comment

Post a Comment

1

Anthony

29 Jul 2012 15:18

I remember much of Sir Viv’s career. Pain featured quite strongly, though I grew to appreciate his greatness in time.

I’m still rather smug about my Doug Walters guess to be honest